This tightly structured, well-acted and workmanlike film is beautifully directed and neatly combines aspects of human behavior and technological dilemma.

Directed by John Sturges

Produced by M. J. Frankovich

Screenplay by Mayo Simon

Based on “Marooned” by Martin Caidin

Cinematography: Daniel L. Fapp

Edited by Walter Thompson

Distributed by Columbia Pictures

Running time: 134 minutes

Budget: $8–10 million

Cast

Richard Crenna as Jim Pruett

David Janssen as Ted Dougherty

James Franciscus as Clayton Stone

Gene Hackman as Buzz Lloyd

Lee Grant as Celia Pruett

Nancy Kovack as Teresa Stone

Mariette Hartley as Betty Lloyd

Scott Brady as Public Affairs Officer

Frank Marth as Air Force Systems Director

Craig Huebing as Flight Director

John Carter as Flight Surgeon

Walter Brooke as Network Commentator

Vincent Van Lynn as Aerospace Journalist

George Gaynes as Mission Director

John Forsythe as The President (voice only)

Tom Stewart as Houston Capcom

Bill Couch as Cosmonaut

1969 Trailer

“Spacecraft systems are go”

The early morning serene stillness slowly heralds the dawning of a new day. At the same time an acronymed and abbreviated staccato countdown proceeds toward another dawning of a new day in which the fabric of Nature’s tranquil curtain is about to be rent by the rude sharp thrust of humanity’s spear of technological optimism.

Three U.S. astronauts (commander Jim Pruett, "Buzz" Lloyd, and Clayton "Stoney" Stone) are to be the first crew of an experimental space station on an extended duration mission.

Their Apollo spacecraft is named, “Ironman One,” conjuring up impressions of Marvelled invincibility and superhuman powers. The mission seems to exude supreme confidence and after a successful launch which appears to be quite routine and within the capsule (despite the bone-jarring lift-off) surprisingly serene and sedate, it is observed by one of the astronauts, “Hey, it looks like a fine day down there! I can see all the way from Gibraltar to Greece. Coming up on the terminator, should be in our first sunset in a few minutes.”

The only thought given to any problem or difficulty seems to lie with obtaining a clearer picture for the cameras.

After 22 minutes into the flight, the crew will set about “the business of the flight plan” involving a rendezvous on docking with the Saturn 4B orbital laboratory. The lab is very much like the Skylab of the 1970s we’re familiar with.

Routine, predictability, training and technology combine to achieve the successful completion of the docking procedure with the orbital laboratory into which the crew of Ironman One will transfer and where they will live and work for the next seven months.

According to the Public Affairs Officer, “this will be a test of the spacecraft, the systems and most of all the men in preparation for interplanetary deep-space missions which are now being planned.”

According to the Public Affairs Officer, “this will be a test of the spacecraft, the systems and most of all the men in preparation for interplanetary deep-space missions which are now being planned.”

Apparently with the moon landings under its belt and with rendezvous and docking procedures along with extra vehicular activities having become something of a walk in the park, humanity is now optimistically setting its sights further afield, perhaps in this case to Mars.

About five months into the mission problems begin to emerge in which it is observed there is a serious decline in the ability to perform simple manual tasks, along with lack of sleep, fatigue and weight loss. Lloyd in particular has begun to exhibit erratic behavior and substandard performance. His physical appearance and demeanor speaks volumes. Equipment is beginning to fail, mistakes are being made and the wrong kind of problems and priorities are being fixated on.

In the face of these developments, NASA management decides to end the mission early.

After closing down the S-4B lab, the Apollo spacecraft prepares for separation followed by automatic sequence of retrofire. Routine, predictability, training and technology should combine to enable them to start their “descent across Australia towards the splash point in the Pacific some 400 miles south of Midway Island.” All they now need to do is wait for confirmation of retrofire….

Space is no place for hubris and over-confidence. If care is not taken and respect is not given, space will kill you. Humans are not evolved to live and work in space for very extended periods of time. The only way that can be achieved is to terraform the new environment or bio-engineer humans to cope with the hostile conditions.

There is only in reality the thin skin of a spacesuit, a spacecraft or habitat that separates one from being alive or being sucked into oblivion. Technology does fail and humans do make mistakes and space is unforgiving of both.

If the recent process of extended lockdowns and social distancing has taught us anything, it is that being social and gregarious creatures, humans can experience difficulties when cut off from normal social activities and interactions. No selection process can possibly anticipate and eliminate all the possible psychological and other group dynamic factors and problems that are likely to occur on extreme long duration space flights and planetary colonization.

Nor will public affairs spin be able to completely and effectively white wash this supposed “successful prelude to the long-term space voyages that some day will be normal and routine…” as after a tense period of attempting to communicate with Ironman One, the message is received, “We have negative retrofire. Negative, no burn.”

Read on for more.....

About five months into the mission problems begin to emerge in which it is observed there is a serious decline in the ability to perform simple manual tasks, along with lack of sleep, fatigue and weight loss. Lloyd in particular has begun to exhibit erratic behavior and substandard performance. His physical appearance and demeanor speaks volumes. Equipment is beginning to fail, mistakes are being made and the wrong kind of problems and priorities are being fixated on.

In the face of these developments, NASA management decides to end the mission early.

After closing down the S-4B lab, the Apollo spacecraft prepares for separation followed by automatic sequence of retrofire. Routine, predictability, training and technology should combine to enable them to start their “descent across Australia towards the splash point in the Pacific some 400 miles south of Midway Island.” All they now need to do is wait for confirmation of retrofire….

“Ironman One, Ironman One, this is Houston CapCom, do you read?”

Space is no place for hubris and over-confidence. If care is not taken and respect is not given, space will kill you. Humans are not evolved to live and work in space for very extended periods of time. The only way that can be achieved is to terraform the new environment or bio-engineer humans to cope with the hostile conditions.

There is only in reality the thin skin of a spacesuit, a spacecraft or habitat that separates one from being alive or being sucked into oblivion. Technology does fail and humans do make mistakes and space is unforgiving of both.

If the recent process of extended lockdowns and social distancing has taught us anything, it is that being social and gregarious creatures, humans can experience difficulties when cut off from normal social activities and interactions. No selection process can possibly anticipate and eliminate all the possible psychological and other group dynamic factors and problems that are likely to occur on extreme long duration space flights and planetary colonization.

Nor will public affairs spin be able to completely and effectively white wash this supposed “successful prelude to the long-term space voyages that some day will be normal and routine…” as after a tense period of attempting to communicate with Ironman One, the message is received, “We have negative retrofire. Negative, no burn.”

Read on for more.....

“We're prepared for every contingency”

Then why has the unexpected happened? Why doesn’t Mission Control know what’s wrong? If “all parameters are normal,” then why didn’t retrofire function as expected?

And so Ironman One continues to trail a line of “why’s” as it traces its orbit in the silence of space to the accompaniment of a single solemn and sustained note drawn from the music of the spheres. No place for a Strauss waltz here!

Mission Control soon comes up with a possible solution to the Apollo crew’s dilemma which involves trying retrofire with their primary engine by using manual command to get ignition as their automatic control system is out.

For news service and public consumption under the directive to “keep it trivial. Keep it routine;”

“We received word from Ironman: One of a malfunctioning switch that has prevented retrofire on their last orbit. They'll bypass the switch. At their next orbit we'll try manual retrofire.”

However it is sensation that sells and the public might very well be confronted by headlines such as these;

IRONMAN PRIMARY ENGINE & THRUSTERS FAIL!

FEARS FOR IRONMAN CREW – MAROONED IN SPACE!

Unfortunately, the Ironman crew’s second attempt at retrofire also fails despite the fact that an indicator event light showed green suggesting that they had retrofired. Somewhere at sometime a butterfly had flapped its wings and now the crew of an Apollo space craft find themselves facing the prospect of being marooned in orbit around the earth. Perhaps the butterfly has long since died….

While the problem facing the crew and the mission is being worked on, an important element is being overlooked – the wives of the astronauts. They have been watching the events unfold and everyone has forgotten about their presence.

“I'm the responsible officer”

The press conference presided over by Charles Keith reminds us of many of the political press briefings we’ve witnessed in which information is massaged, misinformation is disseminated, truth and facts are distorted, fault and blame is apportioned and redirected, and many words are used without much of value being said. In the process, trust in authority is steadily diminished in the eyes of the public.

Keith is the responsible officer for withholding the news about the retrofire malfunction from Washington but he wont make a statement as to why.

A positive spin is being placed on this very serious situation when Keith informs the assembled press that “approximately 15,000 people are trying to isolate and correct this malfunction. Every resource of the NASA and our industrial contractors is being used to the fullest.”

In addition, he states that the crew are “in no immediate danger” despite the fact that if the crew of Ironman One cannot get the engine to fire, the spacecraft will continue orbiting the Earth “until orbital decay slows it down sufficiently for it to re-enter the atmosphere” and it gets burn to a crisp in seven years.

Keith answers this possibility with what can only be described as a lie and rallying call of human hubris: “We're prepared for every contingency.” Countless butterflies are at this moment flapping countless pairs of wings – prepare for that if you can!

For the astronauts there is little to do but wait “for Ground to analyze the entire telemetry” and come up with a plan to bring them down. Jim Pruett is obviously of “the right stuff” generation who relies on his long practical experience to settle into a relaxed state of mind. Buzz Lloyd appears to be not taking the situation well, as can be gauged from his strangulation of the liquid food tube. He prefers to take action, any kind of action rather than sit and wait for Ground to tell them what to do. Lloyd is ruled more by his emotions and is of a more sensitive and imaginative bent than his fellow astronauts. “Stoney” appears to be ruled by logic and analytical thinking. His attention is focused not on the crew’s predicament but instead on the forming hurricane northeast of Cuba – an obvious complicating factor in the film’s plot as we learn that “she's gonna be a big beast.”

There is by now little doubt that the crew are effectively marooned in orbit around the earth. Their space craft does not have enough fuel left to use the reaction control system as a backup to initiate atmospheric entry. Nor do they have enough fuel to re-dock with the station and wait for rescue.

At a meeting presided over by Keith, recommendations for the US president are on the agenda. What stands out is the almost callous and insensitive nature of the proceedings that can only be described as being the product of an overly bureaucratic mindset.

First, a prepared statement is to be issued at the meeting’s conclusion stating that "every effort is being made to discover and correct the spacecraft malfunction in accordance with contingency plans designed to meet such emergencies."

Secondly, a report is to be issued which places a positive spin on the tragedy by “emphasizing the high degree of safety and success in the program thus far.” To add insult to injury “the accident will be compared to the failure of an experimental aircraft” and that “it'll be noted that in the development of such aircraft, a 10 percent pilot loss is considered acceptable.”

Thirdly, for public consumption and political considerations, the president is to issue a speech “emphasizing the courage and determination of the crew and their final wish, that the program be continued without pause.”

It is only Ted Dougherty who speaks up for the Ironman crew to propose launching a rescue mission, but it seems that logic will provide an insurmountable barrier. There seems to be next to no hope for a rescue flight to reach the crew before their oxygen runs out in under two days. In addition, there are no backup launch vehicles available at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. As for using an experimental U.S. Air Force lifting body, the X-RV, and launching it on an Air Force Titan IIIC booster rocket, neither one is man-rated, nor is there sufficient time to put a newly crewed NASA mission together. The Titan IIIC may be on the way to nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station for an already-scheduled Air Force launch, but it is pointed out that many hundreds of hours of preparation, assembly, and testing would be involved.

And the numbers keep adding up and filling in “the big picture”: twelve days + four days + five days + three weeks + $50 million + .02 percent workforce deaths. In Keith’s mind this equation adds up to a rejection of Ted’s rescue proposal - “reduced to digitals and computerized…..A rational approach.”

Ted Dougherty’s only answer to this is to demand as chief astronaut that something be done, even if it means that some of the preparation items be set aside. After all, what can he tell his fellow pilots who are dying? It would be tantamount to leaving wounded or missing fellow soldiers behind in a time of war.

Keith, in his role as head administrator can only prioritize things in terms of the mission’s overall goals and success. In his view, the three astronauts are “professionals” and that all consciences can be salved by assuming they would share the sentiments contained in the platitude: "Take what you've learned. Get on with the next mission." In other words, individuals are expendable. Just something like what a politician might say to justify the deaths of soldiers ordered to fight in wars.

The clash between acting according to one’s feelings and notions of what is right versus conduct based on a set of rules is finally resolved by recognition that there are not only “pilots” up there but “friends” who are “in trouble” and that it is the right thing to do to at least “try to get them down” and trust in those involved to achieve the impossible.

The US President contacts Keith and informs him “as a friend” that he is right in his stance on the Ironman situation “and for the right reasons.” However, he points out to Keith that “if we do it your way, 200 million people are going to start raising hell.” The president goes on to point out that perception (today, "optics" Yuck!) is more important than following logic and that “the world is watching us and what we do about rescuing these men.” To do nothing to rescue the stricken crew “is going to be disaster for me, for you and for your program.”

It seems that not surprisingly political considerations and national prestige are uppermost in the president’s mind as no mention is really made of the necessity of saving the lives of three fellow human beings just because it is the right thing to do.

The extent of the degree of management of the flow of news and information is apparent from the broadcast picked up by the Ironman crew:

The three astronauts are not only battling time and a lack of oxygen, they soon find they are also in a battle with Mission Control and within themselves.

Here are three intelligent and active individuals feeling that their destinies are being decided by desk jockeys with “slide-rules” and who would much rather take the initiative by donning their “hard suits and fix this bird.”

As they prepare for an EVA to work on the engines, the crew is informed that a rescue mission is being put together with a launch to occur in just over 40 hours.

The crew’s desire to take “affirmative action” to repair their vehicle is quashed by Mission Control. Keith informs them that their use of oxygen outside the spacecraft would mean an unacceptable trade-off in oxygen consumption for “passive breathing.” Put simply, they just don’t have the oxygen to spare.

The crew is told that their only option is to “go into low-tide mode,” lower their oxygen pressure, “execute a full emergency power down” and take their pills. This could prove to be psychologically disastrous for the astronauts as it would be far better if they could see themselves as active participants in arriving at a solution to the problem they are faced with.

Not surprisingly, Buzz goes into conspiracy mode and thinks that Mission Control is lying and that “they want us to buy it while we’re sleeping.” In the end the crew agrees to acquiesce to Mission Control’s request and the ship soon powers down - except for that damn little green light…..

Meanwhile, back on Terra-firma, the tension is ramped up with problems with the rescue craft flight simulation as well as with the hurricane which has changed course with eighty-mile an hour winds and heading straight for the launch site. ETA: 7 or 8 hours.

Back in the orbiting space craft, the sleep period monitors seem to correlate with each individual astronaut’s nature and personality. Stoney’s telemetry shows that he is in “deep, dreamless sleep” and has therefore made a “nice adjustment.” Pruett’s having nightmares which is not surprising since he’s “an angry, active guy, frustrated” and feeling helpless. Nor is it unexpected that Buzz has not been taking his pills which doesn’t bode well for his mental and physical stability.

Instructions have been issued by Keith to keep the crew informed instead of busy and to “kid them along.” This almost seems like an insult to their intelligence and the resulting pathetic attempt at humorous patter and banter does nothing to lighten the sense of doom and gloom within the confined interior of the space craft.

Intelligent, educated and professional men with nothing to do are likely to focus their minds on matters that could act to magnify their problems, affect their overall well-being and damage their relationship with one another.

Stoney takes refuge in the job he was trained for - “observe systems under stress.” Pruett of the old school, dolefully reflects on the fact that he has never made enough money “in this business” and that after so many years he doesn’t have a dime. What’s more, he’s now too old to get the Mars shot. (Don’t worry Pruett, you’d still be waiting for another 50 to 100 years before that would ever happen!!!) As for Buzz? Frustrated, neurotic and belligerent.

A crew of three sharing a destiny but separated by light years in terms of who they are as individuals. One sees only purpose in “devotion to truth” which others might view as lacking in imagination. Another has too much imagination and sees and feels and what others cannot. The third clings to reality and experience with which to navigate his way through a constantly changing present into an uncertain future that may no longer have any use for him.

We’ll leave the stranded astronauts for now as they giggle almost hysterically at the absurd irony of the notion that the experts and those in charge “don’t make mistakes.” The pressure valve is released just a tiny bit…...

Rescue preparations are under way with the XRV suspended beneath an Air Force CA3 helicopter on its way to the launch pad. It’s appearance is something like “a thick arrowhead” and has been modified to carry four men. It is definitely a design concept of the 1960s for a shuttle-type re-usable space craft. I think it looks a lot better than the near-autonomous flying tic-tacs that are now beginning to shuttle crew and supplies between earth and the International Space Station.

“I want to talk about a rescue mission”

There is by now little doubt that the crew are effectively marooned in orbit around the earth. Their space craft does not have enough fuel left to use the reaction control system as a backup to initiate atmospheric entry. Nor do they have enough fuel to re-dock with the station and wait for rescue.

At a meeting presided over by Keith, recommendations for the US president are on the agenda. What stands out is the almost callous and insensitive nature of the proceedings that can only be described as being the product of an overly bureaucratic mindset.

First, a prepared statement is to be issued at the meeting’s conclusion stating that "every effort is being made to discover and correct the spacecraft malfunction in accordance with contingency plans designed to meet such emergencies."

Secondly, a report is to be issued which places a positive spin on the tragedy by “emphasizing the high degree of safety and success in the program thus far.” To add insult to injury “the accident will be compared to the failure of an experimental aircraft” and that “it'll be noted that in the development of such aircraft, a 10 percent pilot loss is considered acceptable.”

Thirdly, for public consumption and political considerations, the president is to issue a speech “emphasizing the courage and determination of the crew and their final wish, that the program be continued without pause.”

It is only Ted Dougherty who speaks up for the Ironman crew to propose launching a rescue mission, but it seems that logic will provide an insurmountable barrier. There seems to be next to no hope for a rescue flight to reach the crew before their oxygen runs out in under two days. In addition, there are no backup launch vehicles available at Kennedy Space Center in Florida. As for using an experimental U.S. Air Force lifting body, the X-RV, and launching it on an Air Force Titan IIIC booster rocket, neither one is man-rated, nor is there sufficient time to put a newly crewed NASA mission together. The Titan IIIC may be on the way to nearby Cape Canaveral Air Force Station for an already-scheduled Air Force launch, but it is pointed out that many hundreds of hours of preparation, assembly, and testing would be involved.

And the numbers keep adding up and filling in “the big picture”: twelve days + four days + five days + three weeks + $50 million + .02 percent workforce deaths. In Keith’s mind this equation adds up to a rejection of Ted’s rescue proposal - “reduced to digitals and computerized…..A rational approach.”

Ted Dougherty’s only answer to this is to demand as chief astronaut that something be done, even if it means that some of the preparation items be set aside. After all, what can he tell his fellow pilots who are dying? It would be tantamount to leaving wounded or missing fellow soldiers behind in a time of war.

Keith, in his role as head administrator can only prioritize things in terms of the mission’s overall goals and success. In his view, the three astronauts are “professionals” and that all consciences can be salved by assuming they would share the sentiments contained in the platitude: "Take what you've learned. Get on with the next mission." In other words, individuals are expendable. Just something like what a politician might say to justify the deaths of soldiers ordered to fight in wars.

The clash between acting according to one’s feelings and notions of what is right versus conduct based on a set of rules is finally resolved by recognition that there are not only “pilots” up there but “friends” who are “in trouble” and that it is the right thing to do to at least “try to get them down” and trust in those involved to achieve the impossible.

"Olympus"

The US President contacts Keith and informs him “as a friend” that he is right in his stance on the Ironman situation “and for the right reasons.” However, he points out to Keith that “if we do it your way, 200 million people are going to start raising hell.” The president goes on to point out that perception (today, "optics" Yuck!) is more important than following logic and that “the world is watching us and what we do about rescuing these men.” To do nothing to rescue the stricken crew “is going to be disaster for me, for you and for your program.”

It seems that not surprisingly political considerations and national prestige are uppermost in the president’s mind as no mention is really made of the necessity of saving the lives of three fellow human beings just because it is the right thing to do.

The extent of the degree of management of the flow of news and information is apparent from the broadcast picked up by the Ironman crew:

… “confirmed tonight that the SPS engine failed to fire leaving America's three astronauts in orbit some 285 miles above the Earth, circling the globe every 94 minutes. They are now approaching the west coast of Africa.

No word has been issued as to the cause of the malfunction beyond the statement made by Dr. Keith at the news conference held this morning in that contingency plans have been developed to meet every conceivable emergency….”

“They don't make mistakes, do they?”

The three astronauts are not only battling time and a lack of oxygen, they soon find they are also in a battle with Mission Control and within themselves.

Here are three intelligent and active individuals feeling that their destinies are being decided by desk jockeys with “slide-rules” and who would much rather take the initiative by donning their “hard suits and fix this bird.”

As they prepare for an EVA to work on the engines, the crew is informed that a rescue mission is being put together with a launch to occur in just over 40 hours.

The crew’s desire to take “affirmative action” to repair their vehicle is quashed by Mission Control. Keith informs them that their use of oxygen outside the spacecraft would mean an unacceptable trade-off in oxygen consumption for “passive breathing.” Put simply, they just don’t have the oxygen to spare.

The crew is told that their only option is to “go into low-tide mode,” lower their oxygen pressure, “execute a full emergency power down” and take their pills. This could prove to be psychologically disastrous for the astronauts as it would be far better if they could see themselves as active participants in arriving at a solution to the problem they are faced with.

Not surprisingly, Buzz goes into conspiracy mode and thinks that Mission Control is lying and that “they want us to buy it while we’re sleeping.” In the end the crew agrees to acquiesce to Mission Control’s request and the ship soon powers down - except for that damn little green light…..

Meanwhile, back on Terra-firma, the tension is ramped up with problems with the rescue craft flight simulation as well as with the hurricane which has changed course with eighty-mile an hour winds and heading straight for the launch site. ETA: 7 or 8 hours.

Instructions have been issued by Keith to keep the crew informed instead of busy and to “kid them along.” This almost seems like an insult to their intelligence and the resulting pathetic attempt at humorous patter and banter does nothing to lighten the sense of doom and gloom within the confined interior of the space craft.

Intelligent, educated and professional men with nothing to do are likely to focus their minds on matters that could act to magnify their problems, affect their overall well-being and damage their relationship with one another.

Stoney takes refuge in the job he was trained for - “observe systems under stress.” Pruett of the old school, dolefully reflects on the fact that he has never made enough money “in this business” and that after so many years he doesn’t have a dime. What’s more, he’s now too old to get the Mars shot. (Don’t worry Pruett, you’d still be waiting for another 50 to 100 years before that would ever happen!!!) As for Buzz? Frustrated, neurotic and belligerent.

A crew of three sharing a destiny but separated by light years in terms of who they are as individuals. One sees only purpose in “devotion to truth” which others might view as lacking in imagination. Another has too much imagination and sees and feels and what others cannot. The third clings to reality and experience with which to navigate his way through a constantly changing present into an uncertain future that may no longer have any use for him.

We’ll leave the stranded astronauts for now as they giggle almost hysterically at the absurd irony of the notion that the experts and those in charge “don’t make mistakes.” The pressure valve is released just a tiny bit…...

“You're letting us say goodbye”

But wait! Of course, there’s a complication. The hurricane has turned and is heading straight for the launch site despite having earlier been predicted to head out to sea. Yet again, we have the question being asked: “How in the hell can they make a mistake like that?” After all, they don’t make mistakes, do they? Another god-damned butterfly flapped its wings somewhere!

The wives are now brought to the control room to speak to their husbands and are cautioned that they will notice “some degeneration” but that they are nevertheless to show their husbands how confident they are. The wives know that they are there to say goodbye.

What can one say to a loved one in such circumstances?

As Celia begins speaking with her husband, Frank she latches on to everyday trivial matters like his fathers’ cold, buying new shoes, losing a bill to the insurance – anything mundane that avoids the unthinkable. Frank the realist and practical man, believes he knows the score and just wants to let Celia know how much he loves her, that she can depend on his friend Dougherty after he’s gone, and that she is to remember that he “had a real good day today.”

Stoney doesn’t express his emotions as one might expect. His feelings are more internalized as his wife reaches out to him via some banter about her “little project” in which her “experimental hypothesis” consists of missing him like mad and how positively his paper was received. Stoney’s feelings then abruptly break through to the surface in a fierce display of optimism and belief that they’ll indeed make it back. For him, perhaps it’s not just all in the numbers after all – “remember that.”

Betty has to witness the mental and emotional collapse of her husband, Buzz. It is almost impossible to witness the sudden degeneration of a loved-one before your very eyes and not be able to do anything about it. You don’t want to remember the unrecognizable stranger that person has become and would rather hold on to the image of the person you knew and loved throughout your life. We’re only human after all and sometimes the urge to run and escape from what terrifies and overwhelms us is too strong.

“Because of men like these, we've taken the first step off this little planet.”

As launch time approaches, the hurricane batters the launch area and threatens to cancel the mission. The tension mounts as the countdown proceeds and wind speed picks up. All personnel in the control room are advised “that prior to 1:20, we'll call a hold if we have a problem.”

At just after T-minus two minutes, we learn that the launch site is “now beginning to feel the real force of Hurricane Alma...”

A sense of doom, defeat and inevitability soon descends on Mission Control and within the space craft. Pruett’s words convey an acceptance of the crew’s likely fate as he stoically informs those on the ground that “whatever happens to us, you can't let it affect the program. You've done a great job, really…..it's nobody's fault.” Then the signal is lost.

After a brief statement to the press, Keith answers questions put to him concerning the fate of the space program, an investigation of the accident, our purposes in space and the morality of putting men into space without adequate (fill in the word – safeguards? preparation?) and whether the results gained are worth the lives lost. All very necessary questions to ask and which should always be considered. We’ll be in trouble if we ever stop asking such questions.

Keith’s response is also both expected from his position and vantage point and quite valid. He believes that because of men like these, we've taken the first step off this little planet” on our way “to the stars, to other worlds, other civilizations” and that inevitably “men will be killed in this effort.”

This was true at the start of the age of space exploration and will continue to be the case long after Space – X and Virgin Galactic become a distant memory. We are going to lose lives in space as a result of unforeseen accidents, equipment failures, human error, over confidence, taking short cuts, cost cutting, bad luck, fluttering butterfly wings and so on.

Suddenly a weather technician breaks in and interrupts Keith in mid-sentence to inform him that the eye of the storm will pass over the Cape permitting a launch of Dougherty’s rescue vehicle to rendezvous with the Apollo command module hopefully in time to save the crew.

Dougherty will have to rendezvous without an onboard computer program but he is confident he can if Mission Control can get him “in the ballpark.” That’s good enough for Keith who proclaims, “Then we are go for launch!”

In the meantime, the Soviet Union has launched a Voskhod on an unspecified mission as the NASA rescue mission launch is made just as the eye of the storm passes over the Cape and the winds begin to rise.

Keith cuts through all the extraneous procedural matters and qualifications and gets to the heart of each matter. One in particular involves oxygen consumption and the fact that there’s not enough oxygen left for three men in the amount of time that’s available.

The inescapable conclusion is that there might be sufficient oxygen for two men to make it. A moral and ethical decision will need to be made at some point – soon.

And so the countdown to launch resumes while outside there’s “no wind, absolute silence. Overhead nothing but black night and brilliant stars...There's an eerie hush over everything here. No rain, no wind. The lives of three men are measured by their fading heartbeats...”

There’s been an 180° turn around in attitude and priority in terms of the value placed on human life that was evident at the earlier meeting presided over by Keith at the start of the engine failure problem. One of the reporters on the scene at the rescue mission comments that the service tower is expendable, “but the three men in Ironman One are not”

As the countdown to launch proceeds, the tension is highlighted by the rapid-fire sequence of camera shots of Keith, the astronauts’ wives, the control room personnel, the countdown status board and so on.

After the successful launch of the rescue craft, we return to the suffocating atmosphere of despondency within the claustrophobic confines of Ironman One. Stoney deals with the situation in his characteristic way by enumerating the effects of anoxia. None of the crew even seem particularly interested in responding to Houston CapCom. After all, what could they possibly offer them?

Pruett finally responds to Keith who informs the crew that they successfully launched the rescue craft through the eye of the hurricane and that it’s on its way to rendezvous with them in 55 minutes time.

This leads to the issue of oxygen supply which Keith is gradually trying to guide the crew’s thinking towards. His unconscious rubbing of his neck suggests someone who is desperately walking on egg shells while trying to avoid coming to the point about something too confronting and unthinkable.

In Fifty-five minutes the crew will be dead if they continue to use oxygen at their present rate of consumption. As to what can be done about this, Keith tells them almost cryptically, “you must think,” that they must talk it over and that “any effective action must be taken immediately.” Earlier, such considerations would have been settled in Keith’s mind based on logic, what the numbers say and what procedure would determine. Not so easy when one has to speak directly with those being impacted and basically having to inform them in one way or another that they must decide which one of them is to die in order for the other two to live.

With the unthinkable decision to made now firmly in their hands, the crew of Ironman one debate what to do. Stoney draws on reason and suggests they “figure the odds” whereby they might survive by taking double the amount of sleeping pills to reduce oxygen consumption. Pruett rejects his idea as being unlikely to conserve enough oxygen to be successful. Lloyd offers to leave since he’s “the weakest” and is "using up the most oxygen." Pruett overrules him and instead orders his crew mates to don their helmets while he attempts to fix the engine, despite the fact that this option has already been dismissed by mission control.

It is pretty apparent that Pruett being the veteran, the commander and an experienced practical and realistic man, has already taken the decision and the responsibility for who is to be sacrificed so that others may live. Keith cannot make such a decision, Mission Control cannot make such a decision. Nor can his crew mates for whom he is responsible make such a decision.

After Pruett goes out of the hatch, Lloyd at first seems to want to believe he is going to fix the engine but he really knows as well as Stoney does what Pruett intends to do. Loyd then makes a move to go after Pruett and stop him. Stoney, however restrains Lloyd to prevent him from ripping the umbilicals they are attached to.

As both astronauts watch Pruett from the hatch, a hiss of air escapes his suit from a large gash torn on a part of the ship’s exterior. Losing consciousness, Pruett drifts away from the ship as Lloyd and Stoney look on.

Pruett’s wife is told about her husband’s death by Keith over the phone. Imagine having to learn of something like that via a phone call. It is obvious, however that she already knew from the moment she left the observation booth as did the others present judging from their body language. For her benefit she is informed that her husband died in the performance of his duty while attempting to repair the spacecraft.

Back in Ironman One, Stoney has to contend with a delirious and almost infantile Loyd along with the effects of oxygen deprivation. His mind alternates between his anchor of rational thought and an unaccustomed hallucinatory state of consciousness brought about by the lack of oxygen.

With the sudden appearance of the Soyuz spacecraft, Keith attempts to engage Stoney with the familiar kind of logical and procedural mind-set he usually operates on. Nevertheless, Stoney struggles to comprehend the cosmonaut's gestures or comply fully with Keith's instructions.

The Soviet ship cannot dock with the Apollo command module but it does have a life-saving supply of oxygen. Stoney and Lloyd are instructed to open the hatch using the lever but under no circumstances are they to blow the hatch. Loyd in his delirious state of mind of course blows the hatch causing the ship to move further away from the Soyuz craft.

Lloyd and Stoney will now have to traverse 50 feet of space to get to the Russian cosmonaut. After a nudge from Stoney, Lloyd drifts away from the ship and sails past the cosmonaut, just out of his reach.

“Minus 90 seconds and counting”

“T-minus 70 seconds and counting, mark”

“T-minus 60 seconds and counting….”

THEN AT T-MINUS 60 SECONDS….

“Hold! Hold!”

“Shut her down!”

“The launch is scrubbed”

“The launch is scrubbed”

After a brief statement to the press, Keith answers questions put to him concerning the fate of the space program, an investigation of the accident, our purposes in space and the morality of putting men into space without adequate (fill in the word – safeguards? preparation?) and whether the results gained are worth the lives lost. All very necessary questions to ask and which should always be considered. We’ll be in trouble if we ever stop asking such questions.

Keith’s response is also both expected from his position and vantage point and quite valid. He believes that because of men like these, we've taken the first step off this little planet” on our way “to the stars, to other worlds, other civilizations” and that inevitably “men will be killed in this effort.”

This was true at the start of the age of space exploration and will continue to be the case long after Space – X and Virgin Galactic become a distant memory. We are going to lose lives in space as a result of unforeseen accidents, equipment failures, human error, over confidence, taking short cuts, cost cutting, bad luck, fluttering butterfly wings and so on.

“The numbers, Mr. Keith, the numbers!”

Suddenly a weather technician breaks in and interrupts Keith in mid-sentence to inform him that the eye of the storm will pass over the Cape permitting a launch of Dougherty’s rescue vehicle to rendezvous with the Apollo command module hopefully in time to save the crew.

Dougherty will have to rendezvous without an onboard computer program but he is confident he can if Mission Control can get him “in the ballpark.” That’s good enough for Keith who proclaims, “Then we are go for launch!”

In the meantime, the Soviet Union has launched a Voskhod on an unspecified mission as the NASA rescue mission launch is made just as the eye of the storm passes over the Cape and the winds begin to rise.

Keith cuts through all the extraneous procedural matters and qualifications and gets to the heart of each matter. One in particular involves oxygen consumption and the fact that there’s not enough oxygen left for three men in the amount of time that’s available.

The inescapable conclusion is that there might be sufficient oxygen for two men to make it. A moral and ethical decision will need to be made at some point – soon.

“In the middle of another heartbeat”

And so the countdown to launch resumes while outside there’s “no wind, absolute silence. Overhead nothing but black night and brilliant stars...There's an eerie hush over everything here. No rain, no wind. The lives of three men are measured by their fading heartbeats...”

There’s been an 180° turn around in attitude and priority in terms of the value placed on human life that was evident at the earlier meeting presided over by Keith at the start of the engine failure problem. One of the reporters on the scene at the rescue mission comments that the service tower is expendable, “but the three men in Ironman One are not”

As the countdown to launch proceeds, the tension is highlighted by the rapid-fire sequence of camera shots of Keith, the astronauts’ wives, the control room personnel, the countdown status board and so on.

After the successful launch of the rescue craft, we return to the suffocating atmosphere of despondency within the claustrophobic confines of Ironman One. Stoney deals with the situation in his characteristic way by enumerating the effects of anoxia. None of the crew even seem particularly interested in responding to Houston CapCom. After all, what could they possibly offer them?

Pruett finally responds to Keith who informs the crew that they successfully launched the rescue craft through the eye of the hurricane and that it’s on its way to rendezvous with them in 55 minutes time.

This leads to the issue of oxygen supply which Keith is gradually trying to guide the crew’s thinking towards. His unconscious rubbing of his neck suggests someone who is desperately walking on egg shells while trying to avoid coming to the point about something too confronting and unthinkable.

In Fifty-five minutes the crew will be dead if they continue to use oxygen at their present rate of consumption. As to what can be done about this, Keith tells them almost cryptically, “you must think,” that they must talk it over and that “any effective action must be taken immediately.” Earlier, such considerations would have been settled in Keith’s mind based on logic, what the numbers say and what procedure would determine. Not so easy when one has to speak directly with those being impacted and basically having to inform them in one way or another that they must decide which one of them is to die in order for the other two to live.

With the unthinkable decision to made now firmly in their hands, the crew of Ironman one debate what to do. Stoney draws on reason and suggests they “figure the odds” whereby they might survive by taking double the amount of sleeping pills to reduce oxygen consumption. Pruett rejects his idea as being unlikely to conserve enough oxygen to be successful. Lloyd offers to leave since he’s “the weakest” and is "using up the most oxygen." Pruett overrules him and instead orders his crew mates to don their helmets while he attempts to fix the engine, despite the fact that this option has already been dismissed by mission control.

It is pretty apparent that Pruett being the veteran, the commander and an experienced practical and realistic man, has already taken the decision and the responsibility for who is to be sacrificed so that others may live. Keith cannot make such a decision, Mission Control cannot make such a decision. Nor can his crew mates for whom he is responsible make such a decision.

After Pruett goes out of the hatch, Lloyd at first seems to want to believe he is going to fix the engine but he really knows as well as Stoney does what Pruett intends to do. Loyd then makes a move to go after Pruett and stop him. Stoney, however restrains Lloyd to prevent him from ripping the umbilicals they are attached to.

As both astronauts watch Pruett from the hatch, a hiss of air escapes his suit from a large gash torn on a part of the ship’s exterior. Losing consciousness, Pruett drifts away from the ship as Lloyd and Stoney look on.

Pruett’s wife is told about her husband’s death by Keith over the phone. Imagine having to learn of something like that via a phone call. It is obvious, however that she already knew from the moment she left the observation booth as did the others present judging from their body language. For her benefit she is informed that her husband died in the performance of his duty while attempting to repair the spacecraft.

Back in Ironman One, Stoney has to contend with a delirious and almost infantile Loyd along with the effects of oxygen deprivation. His mind alternates between his anchor of rational thought and an unaccustomed hallucinatory state of consciousness brought about by the lack of oxygen.

The Soviet ship cannot dock with the Apollo command module but it does have a life-saving supply of oxygen. Stoney and Lloyd are instructed to open the hatch using the lever but under no circumstances are they to blow the hatch. Loyd in his delirious state of mind of course blows the hatch causing the ship to move further away from the Soyuz craft.

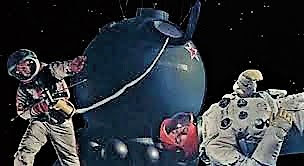

Dougherty arrives on the scene in the X-RV and begins a spacewalk to retrieve the astronauts. The Soviet cosmonaut uses a torch to shine a light on the body of Lloyd who is drifting slowly away from the Apollo space craft. Dougherty retrieves him using a maneuvering pack, similar to the kind that will be used later in the 1980s.

After moving his vessel closer to the Apollo craft, the cosmonaut enters the Apollo and tries to attach an incompatible oxygen tank onto Stone's suit. Dougherty returns with Lloyd and transfers his oxygen to Stoney’s suit helping to further revive him.

In a nice piece of detente which will be a feature in later missions of the 1970s, the two surviving Ironman crew members are transferred to the rescue ship. Meanwhile, on the ground there is utter pandemonium as everyone erupts with jubilation and sirens wail as if an enormous pressure valve has suddenly been opened.

After the rescue, the X-RV executes retrofire to return to Earth and the Soviet vessel returns to its previous orbit. The final scene then fades out with the image of an abandoned Ironman One adrift in orbit.

Points of Interest

The film was released less than four months after the Apollo 11 Moon landing and there must have been pressure to achieve as much realism and authenticity in its depiction of the Apollo mission.

NASA, along with North American Aviation and Philco-Ford, assisted with the design of the film's hardware, including the crew's chairs inside the capsule, the orbiting laboratory, the service module, as well as replicas of actual facilities, such as the Mission Operations Control Room at Johnson Space Center in Houston and the Air Force Launch Control Center at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station.

In fact, the Apollo Command Module used in making the film was an actual "boilerplate" version of the "Block I" Apollo spacecraft.

When “Marooned” was eventually produced with John Sturges as director and Mayo Simon as screenwriter, the budget was $8 million. It went on to win an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for Robie Robinson.

You’ll notice that in the film the central role of a flight director is absent. It may have been felt that the inclusion of a flight director in that role might distract from the tense interplay and clash of wills and personalities between Keith and Dougherty.

The tragic fate of the Apollo 1 crew would have been fresh in people’s minds adding poignancy to the dilemma being faced by the on-screen crew of Ironman One. “They never make mistakes, do they?”

In many ways, the film was strangely prescient in light of what later occurred with the actual Apollo 13 mission. According to astronaut Jim Lovell, a certain un-named 1969 film in which another ‘Jim’ (Pruett) faces death in space had given his wife nightmares. Fortunately, both the film and Apollo 13 crews got back alive with the exception of course of Pruett in the film. For the Apollo 13 crew, the need for the astronauts to be a part of the overall plan and solution to the problem being faced was extremely important.

Speaking of astronauts’ wives, it might be tempting for some people to view the three women featured in the film as being just stereotypical females of the 1960s fulfilling their expected roles as dutiful wives of men who charge around doing manly stuff. I find these women, however to be far more interesting, relatable and believable than many modern female characters in an opportunistic film industry who are often portrayed in an unedifying manner as angry, sinewy, sweaty, ponytail swishing, active wear clad action heroes with a penchant for beating up men and assaulting their genitals!

The three astronauts’ wives in the film perhaps have the most difficult and nightmarish role imaginable and it shows clearly through their words and gestures. On-screen female characters that possess and convey class, poise and style hold far more interest and value than many of today's obnoxious film harpies.

In fact, the Apollo Command Module used in making the film was an actual "boilerplate" version of the "Block I" Apollo spacecraft.

When “Marooned” was eventually produced with John Sturges as director and Mayo Simon as screenwriter, the budget was $8 million. It went on to win an Academy Award for Best Visual Effects for Robie Robinson.

You’ll notice that in the film the central role of a flight director is absent. It may have been felt that the inclusion of a flight director in that role might distract from the tense interplay and clash of wills and personalities between Keith and Dougherty.

The tragic fate of the Apollo 1 crew would have been fresh in people’s minds adding poignancy to the dilemma being faced by the on-screen crew of Ironman One. “They never make mistakes, do they?”

In many ways, the film was strangely prescient in light of what later occurred with the actual Apollo 13 mission. According to astronaut Jim Lovell, a certain un-named 1969 film in which another ‘Jim’ (Pruett) faces death in space had given his wife nightmares. Fortunately, both the film and Apollo 13 crews got back alive with the exception of course of Pruett in the film. For the Apollo 13 crew, the need for the astronauts to be a part of the overall plan and solution to the problem being faced was extremely important.

Speaking of astronauts’ wives, it might be tempting for some people to view the three women featured in the film as being just stereotypical females of the 1960s fulfilling their expected roles as dutiful wives of men who charge around doing manly stuff. I find these women, however to be far more interesting, relatable and believable than many modern female characters in an opportunistic film industry who are often portrayed in an unedifying manner as angry, sinewy, sweaty, ponytail swishing, active wear clad action heroes with a penchant for beating up men and assaulting their genitals!

The three astronauts’ wives in the film perhaps have the most difficult and nightmarish role imaginable and it shows clearly through their words and gestures. On-screen female characters that possess and convey class, poise and style hold far more interest and value than many of today's obnoxious film harpies.

I wonder if "Marooned" will eventually fall victim to the band-wagon virtue-signaling depredations of the Cancel Culture Cult.

In many ways, I actually preferred this film to something like “2001, A Space Odyssey” as it seemed to be far more grounded in reality, rather than trying too hard to trip over itself with prolonged orgiastic visual psychedelics to the accompaniment of Strauss. With the then recent moon landing, the film hints at what may be possible just on the horizon such as preparation for a Mars mission (well, ok we know what happened to that dream!), an orbiting laboratory like the later Skylab and the rescue vehicle being a prototype for the later re-usable Shuttle, as well as a hint of detente and cooperation in space. Then there is the element of human drama involved along with the ever-present danger of being a part of space exploration.

If you think that last feature didn’t amount to much, try holding your breath for a couple of minutes!

©Chris Christopoulos 2021

©Chris Christopoulos 2021

No comments:

Post a Comment